Perusing the diary notes of my grandfather’s brother, Ninio Serretta recently, I was struck by the similarity of the circumstances when his family emigrated from Sicily to England in 1898, and then to South Africa and when my family emigrated from South Africa to England in 1998, exactly 100 years later! Ninio’s family consisted of himself and his brother, Giovanni Jr (my grandfather) who were nine and eight years old resp. and their three sisters Maria, eleven, Virginia, six and Ester, four and their mother Maria Concetta Ammirata and their father, Giovanni Serretta Sr. Giovanni Sr was an artist and had no interest in joining the family’s banking business. There was no work for an artist in Sicily, so he left Palermo to make a new life for the family in London, where he thought that he could make a living with his artistic talent. He went to London in 1893, five years before his wife and children joined him.

Reading between the lines, and using the limited facts as I know them, I am of the opinion that it was his father-in-law, Giovanni Ammirata, who arranged for Marie Concetta and the children to finally move to London to join her husband. Evidently the marriage was arranged by the two families in order to consolidate their respective business interests and properties, and was not a happy one. Both families were wealthy with considerable land holdings and properties. Giovanni Ammirata financed the travel expenses of his daughter and grandchildren, purchased a house in London for them, furnished it lavishly and installed a servant come housekeeper. I can imagine him admonishing his son-in-law: “No more excuses! Now you have tour family and a home! Get on with it!” He returned to Sicily shortly thereafter and left his daughter to her new life in England.

I arrived in London in August 1998, looking for a job, and it was three months later before I was joined by my wife, Noelin. Some of my children were already in London and some would follow shortly after. I did not have a wealthy father-in-law to pave the way for my family to start a new life in a strange land. However, we also experienced a degree of non-acceptance and bias towards us as “foreigners” by a lot of the English people, as had my grandfather and his brother. Here is an excerpt from my great-uncle Ninio’s account of their arrival in London in August 1898:

Lucio’s Serretta’s memories of his parent’s emigration to England when he was 9 years old- Quote:

"It was an evening in autumn of 1898 – to be exact, Sunday 24th October. A cloudy sky over the mountains that surround the Bay of Palermo in whose port the small vessel ‘Gallilco – Gallile’ was anchored which we were to board. We were seven, six of us never to return to see our beloved land again. Besides myself there was my mother, my one brother and three sisters. My maternal grandfather accompanied us. We were destined for England where my father awaited us and from whom we had been separated for just under five years. The vessel was bound for the port of Naples and on the morning of the 25th it passed the isle of Ischia,

I had already risen and was on desk when we sighted Naples. Although chilly it was a beautiful sunny day and the sight of Napes with its busy port, Mount Vesuvius on the right and the hills of Pozzuoli on the left was most impressive and a sight never to be forgotten. My mother’s uncle Bartolomeo (Brusco) met us on the quay, and we spent a very pleasant day sight-seeing with his family. The next portion of our journey was by train to Rome, where we arrived at nearly midday on the 26th and left at 10.30pm. We arrived in Genoa on the afternoon of the 27th and took the train to Turin late that night. At Turin, we stayed at a Hotel and had our meals there. I was very cold. As we came from a warm country, we had no overcoats and warm clothing and my grandfather bought some for us. By this time the children were already getting rather too much for my poor mother. Ester was a baby of four. I remember my sister Virginia had a stomach disorder. My brother John wandered off in the crowd and got lost when we were sight-seeing. It was very tiring for a woman with five children. We left Turin at night the next day 29th October on a train to cross the frontier at Modena on our way to Lyon, where we again changed trains to Dijon and again to Paris. It was just terrible taking our entire luggage off one train to load on another in the dead of night.

We arrived in Paris on the night of the 30th, and had to stay on the station until daylight and then transferred to the Gare Saint Lazare. We wandered around Paris in a carriage all day and had a good meal at one of the Boulevard Restaurants. At 9.30 pm our train left for Calais to cross to Dover. The crossing was dreadful. A big storm got up. The small vessel was crowded with people of all types, many from Russia and Bulgaria. Everybody was seasick and rolling from one side of the salon to the other as the vessel swayed. Although we boarded the vessel at about 1:30am it took over three hours to cross the channel. It was still very dark when we landed at Dover, but we were soon helped into a train. As it was getting light we were able to see the country around us. It was Sunday morning, 1st November 1898. The country all over was covered in snow and we shivered and cried with the cold, but we very soon arrived at Charing Cross Station in London where we expected to see our father again after 5 years. My mother could not believer that she would set eyes on him. She was filled with anger and resentment towards him. I remember grandfather warning her to be calm and forgiving and to look forward to a new and happy life even though it would have its trials.

But it was difficult to calm her. My father was on the station awaiting us. He was tall and wore a warm light brown overcoat. He was good looking. He received us very happily but my mother was very cool to him. We went to another platform on the other side of the station to board another train. We though that very strange as we had not imagined London to be so big. The train took us to Clapham junction about 4 ½ miles, and from there we went to a house in Swanage Road, Wandsworth Common in a horse drawn cab. Everywhere was snow. The road had about 18cm snow. All the roofs and gardens were covered. We alighted and the door was opened by a young woman servant with a black frock and white cap and apron. The house was magnificently carpeted in red plush heavy Wilton throughout. We were first taken upstairs to our bedrooms which all had double beds and bathrooms. We changed into what new clothing my mother had been able to buy for us and then we came down to the dining room. Fires were burning in the grates and all lights were on. The dining table was fully dressed and the sideboard was laden with food. Hams, cheeses, fine rolls of bread and many other things – all ready for us. We all sat down to a meal, my father explaining that in England it was the custom to have breakfast.

Being hungry, we all had plenty to eat. The servant was doing her best to make us understand. She took us to the kitchen where a big fire was burning in the grate, and utensils and crockery were on the shelves. My sister wanted to inspect inside the pantry and she cried “Mama! Mama! Come and see all the food!” We were all enchanted and asked many questions. My brother John was curious to know what was inside some jars on a shelf. My father said it was jam, but no one knew what jam was. My father explained that it was fruit cooked with sugar, and as we had always regarded sugar to be a luxury and prohibitive, we were all anxious to taste it. So my father opened a jar and with a teaspoon we all tasted it. What worried us however was that when we pushed the curtain aside there was no sun and only heavy snow. “Do people go out?” we asked. “Yes! Tomorrow, not today. Tomorrow will be Monday and all the people go out. You will see children playing ‘snowballs’ and other games in the snow”. Shivers were running up and down my back and legs as he was saying this! We could not imagine anyone wanting to go out and to play in such weather. Thus, we spent our first day in England.

We passed the next few days indoors in the same way, while my father went away to business in the City. More snow fell, and we were afraid to open the windows and doors. We thought our father very brave to go out in the snow. Saturday came, and my father said he never worked on Saturdays and Sundays, which we thought strange but wonderful. So, he took us all out. We went to St Johns Road, Clapham Junction, where there is a very large shopping centre with very large department stores. One of them was called Harding and Hobbs which was the biggest. My father bought new suits for my brother and myself, and dresses for my mother and the girls. Also shoes and hats. I remember my mother looking very elegant in an outfit made of Scottish tweed, with long skirt, very narrow waist and very wide sleeves, narrow at the cuffs, called ‘leg of mutton’ sleeves. The hat was a Trilby to match and it had a peacock’s feather at the side. My mother said it was ridiculous, but my sister Maria (Marie) liked it very much, so the assistant fitted her out with something very similar. She was only 11 years old, and my mother said she looked 20. So, my father was pleased. We boys had Norfolk suits with straps below the knees, and wool stockings, and nice wool caps to match.

The next day was Sunday and as the weather had cleared a little we were allowed to go out, so we walked a short distance near a railway line. The road was wide and lined with very large oak trees. Maria was wearing her new dress but thought she was too conspicuous and so when people were approaching to pass us Maria would hide behind one of the large trees so that she would not be seen. She cried when we returned home and said she looked like an old woman. My father suggested that it was the red woollen muffler that was too large. My mother laughed and said my father should have known better that to have dressed them both that way. Maria would never wear her outfit again, but my mother kept hers and when Queen Victoria died in 1900 she wore it at the funeral procession. During the following week, one morning, John and I were allowed out again to the Common. We went a little way and noticed a very large field. The snow had melted and it was very green. We saw a group of boys kicking a very large ball, very high. We had never seen this before so we were curious and went near to watch by the iron railing. Then one of the boys came over and spoke to us.

We could not understand what he was saying, but I could see he wanted us to go over the fence onto the green. As we just stood looking at him I understood him to say “you speak?” I replied “Italiano.” He then called to all the other boys – shouting “Forina! Forina!” so they all ran over, about eight or more, aged between 8 and 13 years of age also shouting “Forina! Forina!”. First, the first one then all of them began hitting us. They got us on the ground and punched and kicked us still shouting “Forina! Forina!”. Then they all started to run away and I saw a gentleman in an overcoat and gloves had come over to us, but we could not understand. He took us with him. We were crying. Our faces were bruised and bleeding and our clothes were wet and soiled. The gentleman took us to a nearby house, which long after I got to know on Westside, Wandsworth Common. A very nice lady took us in. She washed us, gave us tea and biscuits and later the gentleman took us around the nearby streets until we were able to recognise our own house. My parents were very upset, but nothing could be done about it. However, I always remembered and later understood the meaning of what to me had sounded like “Forina”. It was Foreigner.

Evidently, they had a dislike for foreigners, which I did not understand then, but later when I could read in English I concluded that certain classes of the English were politically indoctrinated to hate all foreigners. This caused the whole family very great sorrow through the years in England. The months of November and December 1898 were passing and my grandfather’s return to Italy was nearing as he wished to be back for Christmas. However, before his departure he was taken to the City and the West End and to see the sights of London. Christmas came and we saw that the people celebrated immensely and so did we. As we could not speak English we naturally could not make friends even with our neighbours. Early in the New Year my father managed to get us, the three eldest into the local school, which was called ‘The Swaffield Road Primary School’

(Swaffield Primary School is still there now (2021)

Lucio and John suffered severe beatings from bullies, but Lucio who was more aggressive soon learned to defend himself and his brother, who was gentler of the three children, hampered by having to learn a new language and culture, Lucio progressed the best. Maria was relegated to the back of the classroom and given knitting to do by the teacher, who provided her with wool and needles and who’s family benefiting by the supply of socks and stockings." Unquote.

Now I daresay that it would have been much more difficult for such young children in those days to integrate into a new culture, especially children who had never had the opportunity to experience any other culture than their own Sicilian one, which was very cloistered, than it is for children today, who have had exposure to other cultures via the WWW. I, however, did experience resistance from some British people when I first tried to fit myself into the local society, as did my family. I came up against some vehemently unwelcoming individuals who had very preconceived ideas about people from South Africa, even though they knew nothing about me, and even less about that country, but strangely enough, never people of colour. The fact that I was comparatively well educated and was arguably more proficient in the English language than they were, created some great hurdles for me to climb over. I succeeded by demonstrating ability and accomplishment but I had to start at the bottom and work my way up the seniority ladder, re-inventing the wheel that had come to a crashing halt in a political ditch in South Africa. My efforts were also made easier by the fact that I had a better and more disciplined work ethic than the average Brit. This is a fact that applies to most South Africans, Australians, New Zealanders and East Europeans. The average British worker is very unionised, and is more concerned about the length of his tea break than his productivity. South Africans stop work when the job is done, Brits stop work when the clock strikes four-thirty.

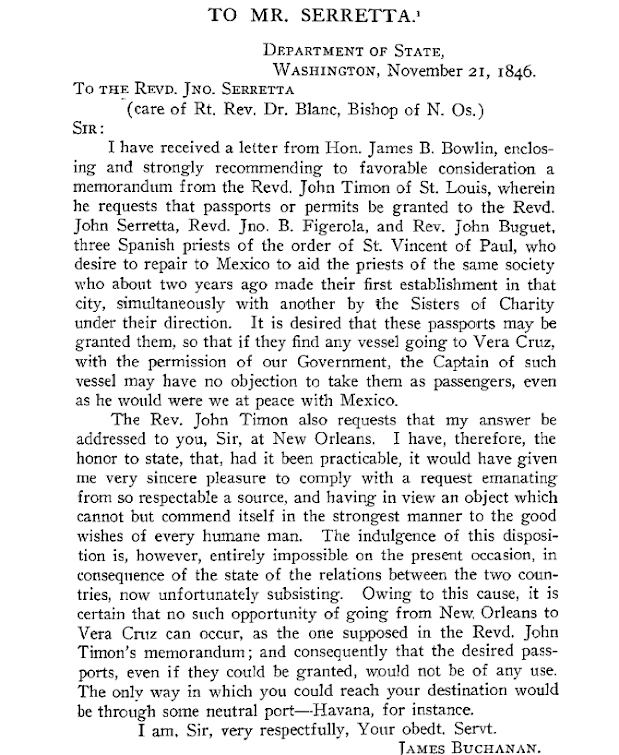

One can only admire Concetta and Giovanni Jr for taking on the huge task of integrating their family into British society, and becoming British. My grandfather, Giovanni Jr (Big John) went on to fight with the British Army at the battle of the Somme in 1915. He drove an ambulance between the front lines and the field hospitals. His ambulance, a commandeered truck, took a direct hit and he was blown into a lake of mud, which saved his life. Nevertheless, he was invalided back to England with burns and concussion. Here is a photo of him and one of him and his crew, taken in Calais in 1914:

Giovanni on the left.